Fireplaces

Reading around various forums, it seems fireplaces are a bit of a contentious issue in listed buildings. The problem seems to stem from the fact that fireplaces have evolved significantly over time. Before chimneys were invented, fires were lit in the centre of the room and smoke would seep through the roof. With the advent of chimneys came large inglenook fireplaces until in about 1790, inventor and physicist Benjamin Thompson discovered that restricting chimney openings improved the airflow, the draw of smoke up the chimney and the efficiency of the fire overall. This resulted in a revolutionary transformation of fireplaces where inglenooks were commonly bricked in to make smaller openings with hob grates. Designs continued to evolve through the Victorian period and the early 20th Century until central heating became more commonplace and fireplaces were either left redundant or removed altogether and the chimney opening bricked up.

As one of the most dominant features in the home, it is quite understandable that people like to appreciate the aesthetic of a fireplace, even if it is not in use. However, if you live in a listed building from say 1750 which was originally built with an inglenook fireplace, the chances are this will have been altered several times over the years. Often, the most recent alterations were made in the 1940s or 1950s in a style that is challenging to common tastes at the current time. The temptation is to remove this incarnation and return it to its original inglenook arrangement but in doing so, you would be removing all those layers of historic alterations and for this reason the chances are, you would be refused permission by the conservation officer…hence a lot of anger in the historic building forums.

I do have some sympathy with the forum rants. I’m not a huge fan of 1950s fireplaces myself, but I do think that most design goes through a natural lifecycle roughly as follows:

- Contemporary (brand new) – valued for being new and cutting edge.

- Dated (about 10-30 years old) – everyone’s a bit tired of looking at it now.

- Retro (about 30-60 years old) – nostalgia for designs that were largely cleared out during their ‘dated’ phase. Appreciated by niche groups.

- Period (over 60 years old) – the ‘dated phase is now a distant memory and design is widely appreciated as a rare and authentic record of its period. The appeal becomes broader the longer ago the period was.

By my reckoning then, 1950s design is in the process of becoming ‘period’ and of increasing appeal, so perhaps those people refused permission to remove their fireplaces will grow to love them over the coming years.

Our own situation was quite different. In this house, all the fireplaces had been removed and bricked up except in the lounge where a wood burning stove sat in a large opening, presumably the original proportions. Having no historic material to remove, we applied for permission to open up the fireplaces to whatever their original proportions were and to restore appropriately. It went as follows…

Dining Room.

Once the gypsum plaster patch was removed, we could see a large opening, similar in proportion to that in the lounge and in our neighbour’s house (the other half of the building) that had been reduced to a Victorian sized opening, but with no fireplace surround. Behind this, some of the bricking-in remained but was loose and falling down as I removed about a ton of rubble and muck. This was an extremely messy job and I had sealed this room from the rest of the house with masking tape around the doors to prevent soot seeping out. What I was left with was the original opening with a slightly loose curved brick lintel and some original lime plaster extending up into the chimney. The hearth was part stone, presumably original, and part tile, presumably Victorian. After some careful thought, this is how I approached the restoration:

- Reinforced the lintel with an iron bar which I bent into shape and screwed to the supporting bricks either side.

- Made good the opening with lime plaster but leaving the original plaster at the back exposed, even though it was damaged and revealed some of the rubble stone wall beneath. Cleaned the original plaster with sugar soap.

- Repaired the hearth with lime mortar leaving the original stones and the Victorian tiles in place.

- Commissioned a corbel shelf to fix above the fireplace.

- Had chimney swept, installed a flue liner and a wood burning stove.

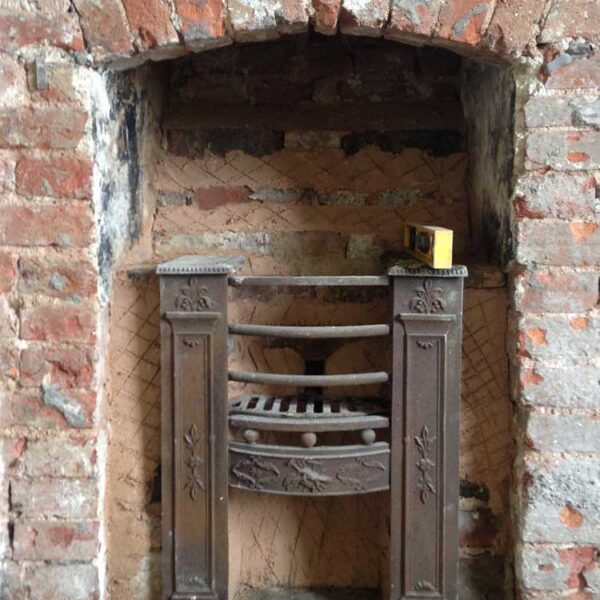

Bedroom.

This was much more straight-forward. The opening was of ‘Thompson’ proportions and the arrangement of bricks behind suggested an iron hob grate was once here, which was consistent with the arrangement in my neighbour’s half of the building. I sourced a hob grate of similar proportions from e-bay, cleaned it up and installed it making good the opening with lime plaster. The joinery company who were reinstating the window shutters and boxes to the same design as the original architrave around the door, supplied me with additional architrave to build the fireplace surround and the shelf to top this off was from a friend’s dad’s collection of salvaged period wood.